New houses for city's homeless evoke old 'hideout'

July 2016 - by Carolyn Dale

In my childhood home, three doors led outside. We children used the front door for the sidewalks and street, and the back door for playing in our yard. We never used the third door, off the kitchen, and it was years before we discovered the fourth door.

Visitors stepped up on the front porch and rang the doorbell. But when the transient men came around West Seattle asking for food or work, in the decades after World War II, they knocked on the kitchen door on the side of the house. We'd be at breakfast—my older brother, the babies, and our mother—after my father had left for the office. Quiet fell after the knocking, as we watched what my mother would do.

She paused from washing the dishes, dried her hands, and peered through the curtained window, then opened the door a crack. "We don't have any work for you," she said. But each time, she told the man to wait a moment, and she wrapped some bread and cheese or leftover meat into waxed paper and handed it through the slightly open door.

I peered from behind her skirt and saw thin white men, some young and some older; they accepted my mother's words and food politely and remained soft-spoken, even humble. Where did they go, when they left with their packets? Where did they sleep?

We'd heard of hobo camps near the beaches and parks and were about to discover a place even closer to home. I remembered it this morning with the news that Paul Allen, a billionaire philanthropist who grew up in Seattle, is funding a complex for the homeless that consists of small, stainless steel compartments. It will be built a few miles from my family's old house; maybe that neighborhood will accept this approach, as well as their new neighbors.

My parents explained, back then, that some men’s lives hadn't got properly started because of the Great Depression, followed so shortly by the war. They had missed out on the normal opportunities of life because of these historic misfortunes that were shared by everyone in our society. They might even “get back on their feet,” if others like us, who were younger and more fortunate, did what we could. That meant giving them food and an occasional odd job, and treating them with respect. "There but for fortune go you, or I," my parents would say.

We saw people's lives in transition all around us. Sometimes we passed gaily painted horse-drawn wagons clopping on the side of the road when we drove from Seattle to Tacoma, and my parents explained that these Gypsy families preferred to travel, moving their homes along with them. This was while we were on the way to visit my great-aunt and uncle, who ran the old family farm until they had to cede it for a hydroelectric project, and it was inundated by the backwater of a dam.

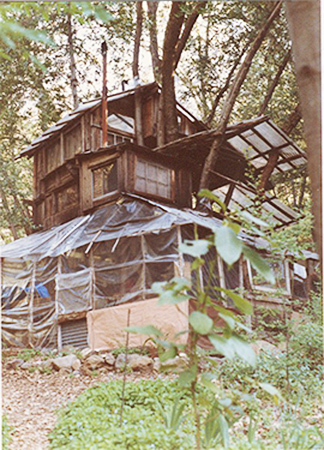

As my brother and I grew older, we explored our yard and the neighbors’ places with less and less supervision. From the kitchen, we clattered down the inside stairs to the basement, a far less civilized space than the upper floors. We ran through the dimness past the old furnace, the stored sleds, skis, and camping equipment, toward the windows and doorway on the far wall that led outside.

Soon we were taking shortcuts by making our own paths through gaps in fences, unlocked gates, and copses of trees, to get to friends’ houses or just to explore. One day, we forged through bracken fern and hazelnut trees on the north side of our own house, and for the first time I stood at ground level and gazed up at the kitchen door, a full story above. Because of the hillside, two stairways approached the landing; the one from the front was short, but the one from the back was long and rose well above our heads.

Wooden siding enclosed the area between the two stairways, forming a triangular shape with the kitchen door at its narrow top. The bottom stretched the width of the house, and a small door had been cut in the siding. It was big enough for a grown-up to crawl through, and it was secured with a little padlock.

"That's probably where they put wood, or coal, in the old days," I said. My parents had bought the house a few years earlier, and the furnace now burned oil.

"Maybe it's a camp, a secret hideout,"my brother said.

We stared at it until we were so scared we had to dash to the safety of the backyard. Weeks passed, it seems, or maybe just days, before my brother nudged me, flashlight in hand, and said he was going to open that little door and look inside. I tagged along, enjoying the delicious thrill of fear.

"What about the lock?" I asked, as we crouched in the bracken fern, whispering. The little doorway looked as though someone had simply sawed out the shape in the siding, attached two hinges, and hung the lock.

"It's broken." My brother yanked on the lock and pulled the door open slightly. It swung easily across a fan of bare, packed earth. Clearly it had been used recently.

"What if somebody's in there?"

My brother tipped the flashlight to shine its beam around the interior, and I peeked over his shoulder. "It's okay. I'm going in. You stay out here and keep watch."

Soon I heard a click and saw dim, swinging light. He had pulled the little chain on a bulb hanging from the floor of the porch overhead. Beyond this bit of wiring, there was no connection between this shelter and the inside of our house.

"Somebody's been living in here," he said, backing out and sitting on his heels.

"Let me see!" I crowded in and saw a thin mattress on wooden pallets over the packed earth, an old wool blanket or two neatly spread on top. Some makeshift wooden shelves held a coffee mug, playing cards, a compass, and a few tiny books or journals.

After a few glances, I backed out, confused and frightened. What if the man who lived here came back just then? My brother reached in to turn off the light, and without speaking, we rushed away.

We loved the secrecy and danger, and since our parents didn't know to forbid us from going inside, we could scare ourselves pleasantly at any time by returning for a visit. And we did. Occasionally we found different furnishings and books; apparently some hobos had more possessions than others. Usually we couldn't read the language of these books but could glean from the illustrations that they were religious.

Within a few years, my father got a new job and we moved to a different city. My parents sold the house, and when movers came to pack our possessions, we children were allowed to put together a box of the things in our rooms that mattered most to us. Thinking of the hideout, I packed a few books.

We did not tell our parents about the hideout then, nor at any time that I remember. Of course we wanted to guard our childhood game, but I think our silence grew out of something more. Perhaps it was the respect we'd been taught for the nature of misfortunes at the time, or simply respect for the privacy of another person's home. Though small and bare, it was attached to our house, and it seemed a genuine, functioning part of our neighborhood, even of our large, prosperous, and growing city.

Back to Timely issues archive